Generally speaking, there are not many African cities that have a modern, well-maintained and efficiently operated fleet of buses.

Generally speaking, there are not many African cities that have a modern, well-maintained and efficiently operated fleet of buses.

National and/or metropolitan authorities have often continued to use standard buses (or conventional buses) without always taking into consideration the urban and operating conditions specific to each city. However, standard buses are rarely efficient in urban areas where the secondary and tertiary road infrastructures are inadequately maintained and lack investment, and in areas where the urban density does not guarantee a minimum demand for public transport (i.e. the outskirts of cities in particular). As a result, vehicles were chosen according to a certain idea of what a traditional bus company should look like rather than an analysis of the operating conditions, thereby ignoring the potential of using smaller-capacity vehicles on certain routes of the network. For example, only Bujumbura (Burundi) or Douala (Cameroon) have recently opted for the use of minibuses.

This penchant of the authorities for standard buses has not prevented the emergence of paratransit services that use medium-sized or even small vehicles (minibuses or equivalent). As a result of, the institutional companies are managing vehicles that are relatively new but poorly suited to the local operating conditions and are facing the competition of a dynamic paratransit sector, which uses minibuses (or equivalent) that are around 25 years old, or even 30 in the most extreme cases.

But the paratransit offer also has its limits. In cities like Abidjan, Dakar or Johannesburg, the supply of minibuses (or other vehicles of comparable size) is far greater than the demand. This oversupply results in inefficiencies and high levels of congestion while the institutional sector does not have enough vehicles to meet demand, and must also comply with the conditions dictated by the minibus sector.

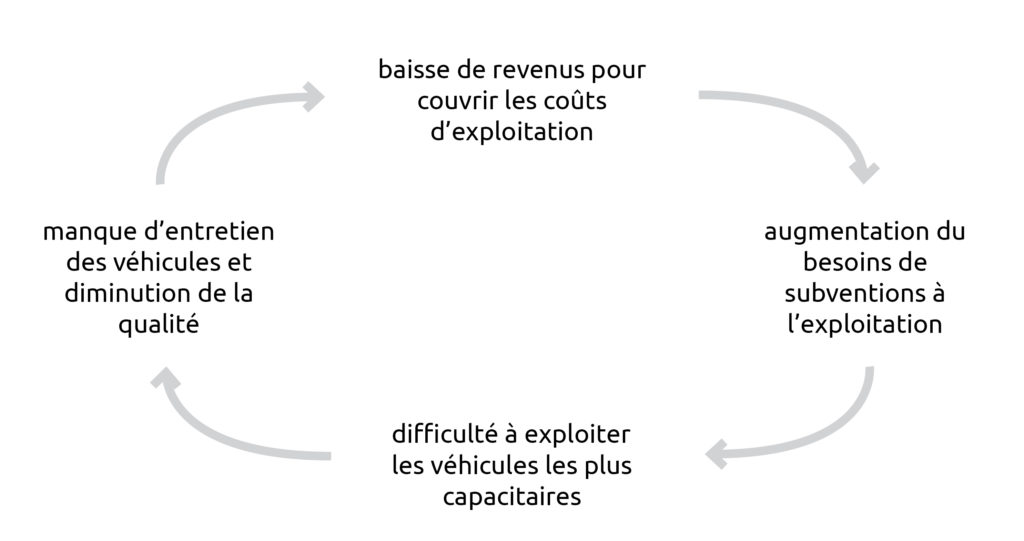

Without any regulation from the authorities, buses and minibuses find themselves in direct competition with each other, to the detriment of the operators of the bigger vehicles. Indeed, the situation only gets worse when these dynamics are not taken into account. The emergence of collective taxi services and, more recently, the surge in motorcycle taxis have also had an impact on the number of bus and minibus users; without a reversal of the trend, buses will be the first to suffer the effects of this unfair competition, and will see their demand decrease and enter a vicious circle that will be difficult to break: without sufficient revenues to cover operating costs, the need for subsidies and lack of investment will increase, leading to operators struggling to run their vehicles because of a lack of maintenance, thereby leading to lower revenues and so on.

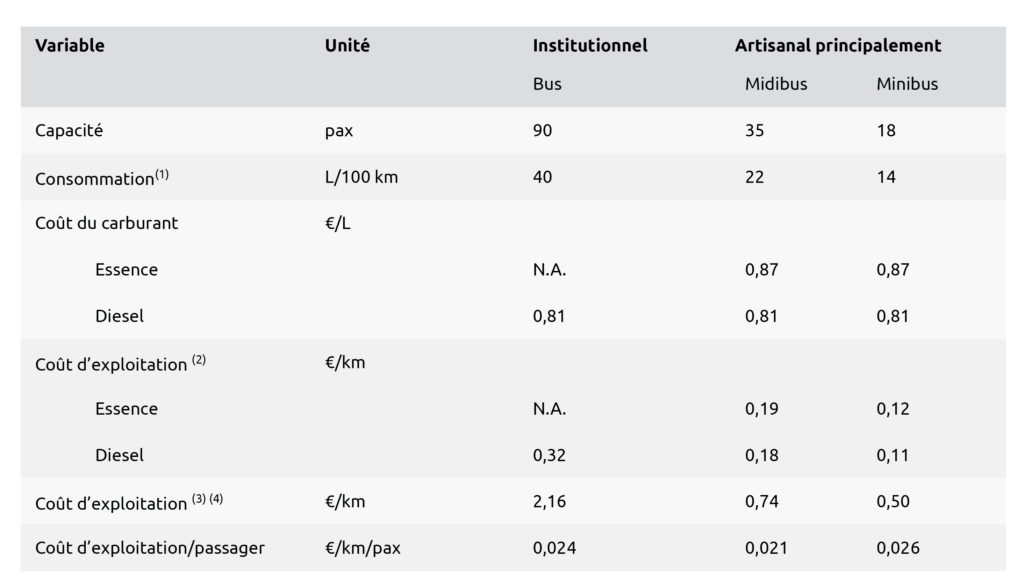

An easy way to compare the performance of transport vehicles is to analyse the operating costs. The investment costs, although high initially, have no direct effect on the operation and daily performance of the vehicles. However, the choice of the type of vehicle used has an impact on performance. According to recent data, the operating costs in €/km are higher for a conventional bus than for smaller vehicles (midibuses and minibuses). Nevertheless, if this operating cost is calculated per passenger, the differences disappear. While this highlights the potential of maintaining conventional bus networks, it is also important to note that, during off-peak periods, the distribution of demand may result in occupancy rates that are lower than is needed to attain comparable operating costs per passenger. Minibuses (or other forms of paratransit transport) can adapt their offer more effectively (by changing their speed or delaying their departure) and be less constrained by the low demand.

Source: Some data from Del Mistro 2015

Notes: (1) 2015 data for a study in the cities of South Africa; (2) Calculated as an average of the fuel price of 40 African countries in July 2018, according to the fr.globalpetrolprices.com website; (3) the result is an average of operating costs by fuel type; (4) To obtain the total operating cost, the assumption was that fuels correspond to 15% of these costs for institutional services and 25% for paratransit services.

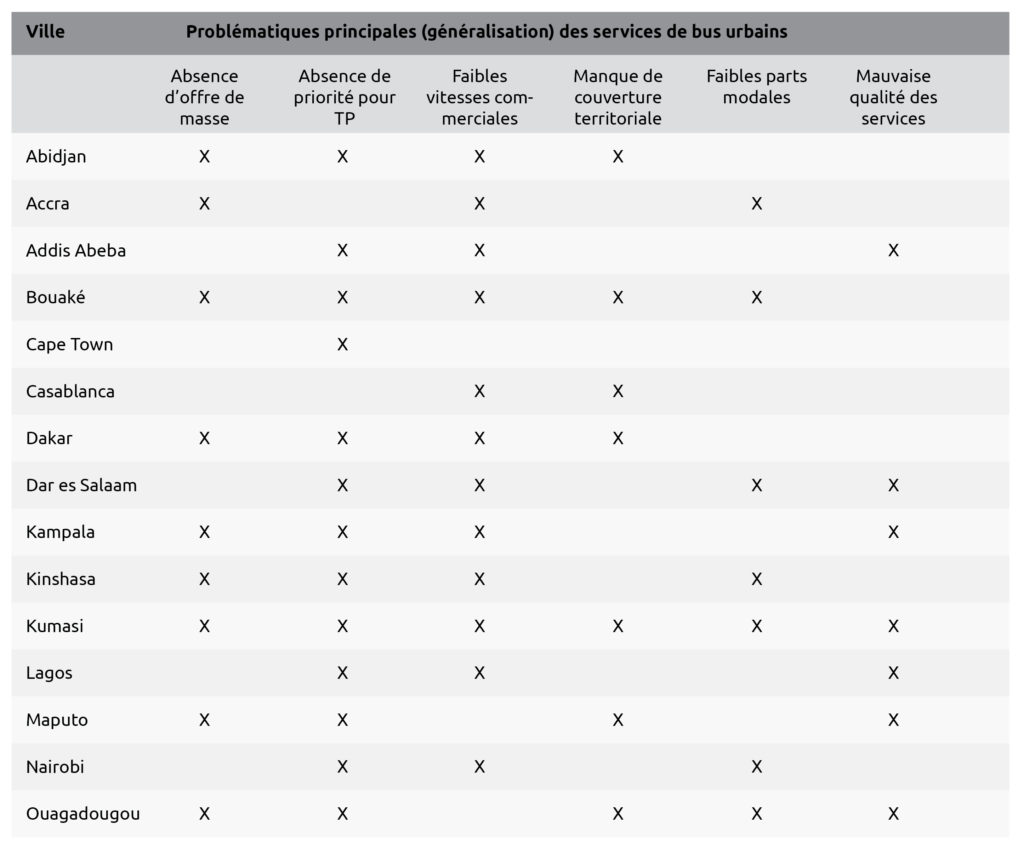

These two problems, i.e. the lifespan of the vehicles and the difficulties in maintaining efficient modern services, had already been highlighted by several studies in the 2000s. Few initiatives have succeeded in reversing the trend, although several cities have embarked on the process of renewing and/or setting up mass transportation networks, including with BRT projects. The analysis of SSATP (Sub-Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program), performed in 2015 on several African cities, highlights the major failures of the current networks and, more generally, the lack of viable mass transit solutions.

Source : SSATP 2015

The solution for renewing the paratransit transport fleet

To deal with the issues surrounding dilapidated vehicles and a general low quality of service in the paratransit sector, one frequently proposed solution is to link the renewal of the fleet with a professionalisation programme for the stakeholders of this sector. Please note that these initiatives are lengthy processes that are onerous for the authorities as well as for the operators. On the one hand, the authorities have to cope with obstacles ranging from the availability of the funding needed to launch programmes, to the challenges of negotiating with the paratransit sector, that is often unwilling to engage in any type of reform. On the other hand, operators suffer from their fragmentary nature, internal conflicts, corruption and a lack of expertise, which is reflected in systematic opposition to any reforms put on the table. Indeed, these difficulties are also the reason why so few initiatives are started or achieve success.

Despite this, initiatives to renew the paratransit public transport vehicles are still seen as realistic and relevant alternatives, which can have positive effects in the medium and long term. The replacement of old – even dilapidated – vehicles meets the objective of improving the quality of service, but also that of reducing the external forces directly linked to the inadequate state of the fleet. With vehicles in better condition operating under similar conditions, CO2 and fine particle emissions are reduced and there are fewer accidents due to mechanical breakdowns. The renewal of the fleet therefore tackles both environmental issues and those of road safety. With initiatives like the “Taxi Recap Programme” in South Africa, it also aims to give operators the option of voluntarily leaving the system with compensation, in order to reduce the number of vehicles on the urban roads and reduce the surplus supply that prevails in a number of cities.

In addition to the replacement of old vehicles, vehicle renewal programmes also include the professionalisation of the paratransit sector. In most cases, professionalisation initiatives arise because the authorities want to consolidate a sector that is too fragmented. They seek to facilitate the consolidation of operator capacities and the beginnings of a new form of corporate structure or grouping of paratransit stakeholders that would develop and eventually become real public transport operating companies. Ideally, once created, these companies will be able to consider engaging in vehicle acquisition or replacement programmes.

The opportunities of setting up a high-capacity bus network

The creation of various forms of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) bus routes or high-capacity bus networks is an opportunity to initiate change in the bus systems of African cities. Nearly two decades after the Latin American BRT revolution, African cities have built few such systems despite the announcement of a number of projects. Lagos and certain cities in North Africa have opted for different more or less heavy forms of BRT. Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) and the South African cities (e.g. Cape Town and Johannesburg) have built projects that tend towards the Bogota or Curitiba version of the BRT model. As for Dakar (Senegal) or Douala (Cameroon), the recent direction they have taken towards a BRT model gives them hope that their networks will become more operational in the years to come. However, with all these examples, the new high-capacity corridors required the acquisition of vehicles with special characteristics that are much more demanding than previously.

Implementing BRT networks entails changes at several levels. First of all, there is a change in terms of vehicle type: the authorities are showing a growing interest in larger capacity buses (they tend to favour articulated or non-articulated buses with high floors rather than low floors, which are currently quite rare) and are ready to seek funding solutions for their purchase. Then, there is a change at the level of the system itself: the new infrastructures must be of a high enough standard to accommodate the high-capacity buses and new models that differ from the buses and minibuses used in the past in African cities. What’s more, the old buses cannot be used on these new routes and have little or no prospects of being integrated into the new network. And, finally, there is a change in the area of operations: the new bus companies, which often have significant private capital, must be able to provide better quality services and comply more closely with certain operating regulations that were previously ignored.

Consequently, the infrastructure-vehicle mix is central to the discussion and will be a factor in deciding between the various options.