As seen above, two systems coexist in most African cities: a high-capacity bus system with a high-quality infrastructure and a system of urban services (including all the collective transport modes from conventional buses to collective taxi services) operating on poorer quality roads. Both systems are not opposed to each other and the metropolitan authorities still need to develop multimodal solutions.

Choices that depend on infrastructure

Within the African urban context, the running of large-capacity buses is directly linked to the available infrastructure.

In principle, there are not as many obstacles to new services like the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) in this area: new infrastructures are built for optimal use.

On these infrastructures, the following two options are available: bus lanes or road links that are strictly closed to other traffic or open – often partially – to other traffic. Routes may be closed in order to guarantee a minimum level of demand for the new BRT services; traditional services (institutional or, mainly, paratransit) are excluded from the route in order to reduce the risk of competition. In this way, the BRTs have a clearer picture of potential revenues. In addition, provided the planning is done properly, it is possible to estimate operating costs with sufficient accuracy and traffic priorities can be planned that will improve speed and reduce operating costs.

The BRT route or network can be opened up when the need arises to tackle other transport issues. However, opening up routes – even partially – can negatively impact the optimisation of operations, given that traditional services are not run according to the same principles and do not focus as much attention on average operating speeds. Traditional buses, whether institutional or paratransit, will obstruct high-capacity vehicles, especially if the overtaking infrastructures only exist at stations.

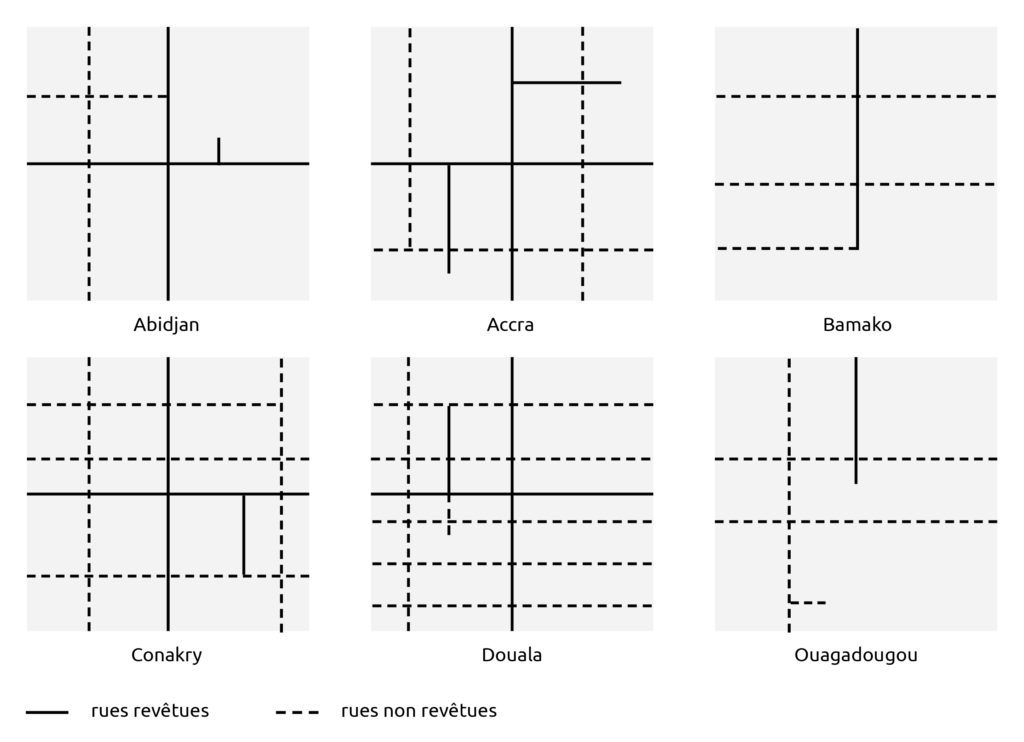

Conventional buses, midibuses, minibuses and collective taxis do not depend on new infrastructures and are operated on low-quality roads. On roads that are unpaved or simply sandy, poorly planned, too steep or on streets with a narrow layout, the higher-capacity vehicles struggle to compete with motorcycle taxis or other types of hyper-flexible services. Minibuses cannot move as easily as collective taxis, which themselves do not have the same freedom as the motorcycle taxis.

The decision to implement new high-capacity buses or new vehicles for secondary or feeder services depends on their capacity to be used in unfavourable circumstances. Envisaging new vehicles with more capacity and less flexibility on poor quality infrastructures is not possible, given the excessively expensive running costs. Without improvements to the road network, investment in new vehicles (high-capacity or not) is unlikely to be a lasting solution.

Source: Kumar & Barrett 2008

Choices that depend on current forms of mobility

In Africa, any initiative to reform public transport by bus must take into consideration the peaks and troughs of the current demand for mobility of the cities concerned. With few exceptions, the cities have monocentric structures with a city centre – or other centre of activity – where most people work (formal and paratransit jobs) and planned or unplanned suburbs that are mainly residential. The demand for mobility therefore follows the urban structure: from residential areas towards the centre of activity at the start of the day and from places of employment towards the outskirts in the evening. The demand is therefore particularly dominated by the daily commute. Indeed, the two morning rush hours represent almost 25% of the total daily demand and the same applies to the evening rush hours, even if this is more stretched out.

These pendular behaviour results in very uneven occupancy rates depending on the direction of vehicle traffic and the time of day. And the lack of profitability in the opposite direction at peak times is all the greater in African countries where the main running cost is the fuel, unlike the northern countries where the main cost is the cost of labour.

The final choice of the vehicle to be purchased must therefore take into account these particular operating conditions. The urban structure may change, but these changes (polycentrism, mixed use, densification, etc.) will take place less quickly than the changes envisaged for the bus fleet. A solution involving a combination of different-sized vehicles would be justifiable in a context like that of African cities.

Choices that depend on the capacity to finance new vehicles

The final aspect to be taken into consideration in a project to purchase vehicles is the limited resources of the national authorities and the even more limited resources of metropolitan or local authorities. Given that mobility is just one of the many other emergencies faced by African cities in terms of improving the living conditions of the local population, the available funds that can be assigned to purchasing vehicles is restricted even further.

In order to find solutions and raise the funds needed to initiate acquisition programmes, African leaders can appeal to financial backers, and they often do. The participation of local stakeholders that could fund a group purchase of vehicles is also possible – Dakar being a case in point – and could be encouraged. (cf. The next step: how to get funding)