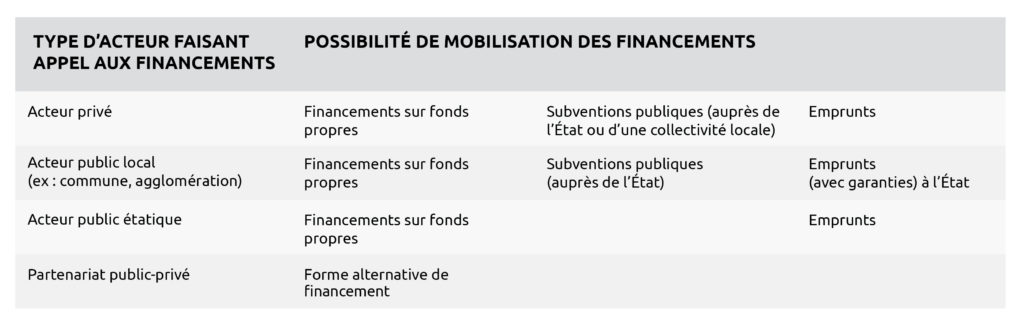

Fund-raising strategies depend on the position/role of the potential buyer. Equity financing, appeals to financial backers, public-private partnerships, etc., are all financing opportunities that will be looked at by private, and local and national public stakeholders.

It will therefore be a question of seeing how it is possible to raise funds using three equity-based strategies:

- from own funds

- by appealing to public authorities

- by borrowing

Equity-based financing

When a stakeholder is looking to fund a bus acquisition project, it can choose to rely on equity. In the accounts of a private stakeholder in mobility, equity, also known as shareholders’ equity, are the resources (liabilities) of a company that belong to its shareholders, as opposed to its debts to suppliers or banks, for example. This accumulation of funds is generally the result of the profits made in previous years (through the sale of bus tickets in particular). For the public stakeholders, the equity allocated to mobility comes mainly from taxes and/or levies.

Nevertheless, it may be necessary to take on debt because the cost of acquiring new buses is often too high for a local authority to be able to bear the entire investment with its own equity. Indeed, the growth in mobility because of population growth and the spreading of communities has led to an ever-increasing demand on public finances to meet investment needs and operating deficits.

Funding of investments by the public authorities

Public authorities, major contributors to the financing of investments in urban transport

On every continent, public authorities represent one of the key contributors to the financing of investment in urban transport. This mode of financing is justified by public service obligations which are generally linked to providing the means of transport for the entire population.

Often, resources are not initially allocated to urban transport and it is a political and budgetary choice that will decide the amounts granted. Since public budgets are conform to an annual budget, urban transport may depend on certain decisions that go against it. Given the long-term nature of urban transport projects, the financing methods whose proceeds are allocated to the “urban transport budget” can provide greater long-term viability.[1]

Mechanisms for financing public investment

With the emergence of decentralisation policies which have resulted in the emergence of new stakeholders at the regional and local levels, public funding is becoming multifaceted with the increasingly important intervention of local authorities and national development banks. While this diversity of sources can be a factor in increasing the funds allocated to transport, it brings with it certain risks of a loss of consistency and efficiency of the investments. By instituting an Public Transport Authority (following the example of the Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (executive council of urban transport of Dakar)), all the resources can be channelled towards objectives planned in the medium and long term, and loans may be obtained from banks and financial backers by offering the guarantee of a stable structure.

Some public schemes for financing investments

- users pay taxes on petroleum products that go to national or decentralised public budgets dedicated to urban transport;

- tolls;

- reinvested operating profit;

- employers pay a tax;

- taxpayers pay taxes;

- borrowing from national or international institutions;

- repayment of a share of the increase in value of the land that is the result of the transport infrastructure according to various methods;

- public authorities’ own budget.

We therefore see that in their need for additional sources to be able to invest in urban transport projects (including the acquisition of a new fleet of buses), which are often very costly, the public authorities call on other institutions. Given the failure of the available public funding options to keep up with changing demand, other sources of funding must be considered.

[1]AFD and CODATU: Guidelines (best practices): Who pays for what in the area of urban transport? (2014 edition) – Chapter 2: Contributors to the public budget for urban transport p. 25

Borrowing to finance the acquisition of new buses

The loans and guarantees are a sensitive issue that should be studied carefully because of the decisive role they play in putting together financial arrangements that are specifically designed for the acquisition of buses. There are two forms of borrowing: by banks or through financial backers.

>> The support of financial backers:

In the public transport sector in developing countries, financial backers play a major role. Each backer focuses its efforts on certain dimensions according to its own expertise and the type of instruments available. Those working mainly on subsidies (US Agency for International Development – USAID –, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit – GIZ – and the Department for International Development – DFID) tend to favour technical aid while the backers that work primarily with loans, e.g. the KFW (KreditanstaltfürWiederaufbau), support financial institutions in expanding their product ranges.[2]

[2] A report co-authored by the Fonds Mondial pour le Développement des Villes (World Fund for Cities Development), Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance (CCFLA) and the UN Environment Programme lists the various backers, that can be mobilised for the climate, on a world map. This provides a fairly broad overview of the different potential sources of funding.

The FMDV offers online training on infrastructure financing.

The intervention of national and international financial partners

Internationally, multilateral banks and bilateral state aid are financing investments in transport systems. Their intervention is not limited to financial loans, and can take several forms[1]:

Donations: they are most often earmarked for studies or institutional aid aimed at improving the design and management of transport systems.

So-called concessional loans: these are loans which may have preferential conditions compared to bank loans in terms of: term, interest rate, grace period (time period granted before the first repayment which generally corresponds to the period preceding the running of the structure). The conditions of these loans differ according to the economic situation of the countries, with the most favourable treatment being granted to the least developed countries.

Untied loans: within the framework of the bilateral Aide Publique au Développement (state aid for development), an agreement has been ratified by the donor countries to prevent this aid from causing distortions to free competition between the countries. The loans and donations may have conditions attached to the use of the funds.

However, for bus fleet renewal projects to succeed, access to borrowing must be ensured by gaining the confidence of lenders. It is thanks to the financial credibility established through the sound management of the financial accounts that the lenders will have the sufficient guarantees for them to invest in such projects. While getting into debt can be risky, carefully managed borrowing can reveal new potential. With every loan, there is a debt. Once it has been contracted, how can the debt be actively managed?

How can the debt be actively managed?

When they are very significant, outstanding borrowings must be managed very closely and renegotiated whenever possible according to changes in interest rates. Given the amounts involved, the gains can be significant. However, the leaders of borrower local authorities are not always concerned about this or do not always have the qualified staff available to manage this. [2]

Active debt management is defined by the local authority’s ability to adapt and develop its outstanding debt in order to minimise the institution’s financial costs at all times. CODATU’s “Who pays what?” guide identifies several financial burden reduction strategies for active debt management:

Analysing the structure of its current debt: developing the main indicators (weighted average rate, duration, average life); creating dashboards of its outstanding debt and structured products; identifying any room for manoeuvre.

Taking advantage of opportunities on current debt: being responsive to market opportunities to make suitable trade-offs; assessing the suitability of renegotiation options; simulating fixed penalties, the point of equilibrium, the actuarial indemnity, the re-employment rate, etc.

Minimising your future debt: choosing between intermediated and non-intermediated financing; defining its selection criteria and preparing for the invitation to tender; comparing the bank offers using the discounting principle, understanding the structured products.

Consequently, it is essential to have a rapid flow of information in order to monitor the permanently changing markets, the banking offer, the financial situation of its structure, and legislative and regulatory developments.

[1]AFD and CODATU: Guidelines (best practices): Who pays for what in the area of urban transport? (2014 edition) – Chapter 2: Contributors to the public budget for urban transport p. 30

[2]AFD and CODATU: Guidelines (best practices): Who pays for what in the area of urban transport? (2014 edition) p. 32

The use of public-private partnerships (PPP) for bus acquisition projects – a brand-new form of financing

The goal of a public-private partnership is to involve the private sector in the initial investment and/or running of a project by entrusting it with some of the tasks, and making it bear some of the risks associated with the project while ensuring that the system is profitable enough (with a public sector subsidy if needed) to be of interest to it.[1]

Public-private partnerships are not strictly speaking a new financial resource. In fact, they are a means of getting the private sector to temporarily bear the financial burden, whether it is for investments or operations. The general principle is that the private partner gradually recovers its costs, either by receiving a repayment from the public authorities, or by receiving a fee from the user of the service and/or infrastructure.

As specified in the CODATU guide: “A public-private partnership can facilitate the contribution of funds to a project in the same way as a loan, except that the lender (the private partner) is recruited and made responsible for the smooth running of the project. In the end, the actual funding will be provided by the users and/or the public sector through the payment of the ticket and/or the remuneration of the private partner, that will be responsible for reimbursing its loans.»[2]

[1]AFD and CODATU: Guidelines (best practices): Who pays for what in the area of urban transport? (2014 edition) – Chapter 7: The use of public-private partnerships p. 111

[2]CODATU: Guidelines (best practices): Who pays for what in the area of urban transport? (2014 edition) – Chapter 7: The use of public-private partnerships p. 115